“There are three ways to ultimate success. The first way is to be kind. The second way is to be kind. The third way is to be kind.” – Fred Rogers

I want to follow up on my previous blog posts about disability etiquette and language with a more advanced topic. (If you haven’t already, you can go over etiquette and awareness basics with our online course). Even the word etiquette is enough to make people feel uncomfortable. It sounds formal and strict, but we learned most of it in kindergarten or from Mr. Rogers. Etiquette is a fancy word for kindness and respect. I want to discuss situations where we accidentally express disrespectful or unkind ideas about people with disabilities. These are often based on some of our unspoken, unwritten societal expectations. It is important to recognize how, in everyday conversations, we may belittle people with disabilities. I'd like to discuss how to not make those mistakes in the future.

A social faux pas is when we do awkward things that communicate something different than what we intended. Here’s one you may recognize: in our society we have an unwritten rule that you should never ask a stranger if they are pregnant. Why? Although you may intend to congratulate them, if they are not expecting, you’ve communicated that you think they’re fat enough to be pregnant. Yikes!

Microagression is one term used to describe these types of accidental unkind messages. Microaggressions occur when we communicate an idea, perception, or assumption that inadvertently excludes or invalidates the worthiness of the other person or the group they belong to. These ideas are a reflection of unanalyzed bias or a commonly-held stereotype about the person’s group. These are often in the form of subtle words, cues, or behaviors, which is why this is a more advanced lesson. A microaggression does not rise to the level of outright hostility, but is insulting to the person receiving the message. You might be able to brush off a few of these if they rarely happened, but some are common and frequently experienced by people with disabilities. They become part of the attitudinal barriers people with disabilities have to overcome.

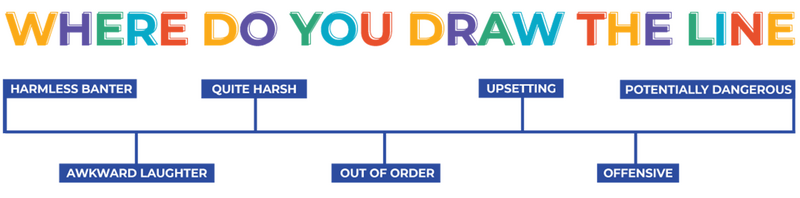

Here are some examples of microagressions people with disabilities commonly experience. Some people may disagree whether some of these “cross the line.” With all social situations, the impact depends on the person and the context. This is your starting point to analyze what you may be communicating if you use these phrases.

- “I could never deal with that.”

- “Your parent/spouse must be a saint.”

- “I’d hate to have [your condition].”

- “I’d kill myself if I had [your condition].”

- “I hope they find a cure for [your condition].”

- “I’ll pray you’ll be healed one day.”

- “I’m so sorry.”

People with disabilities don’t want your pity. Their condition is part of their life; for some it is a positive aspect of their identity, for other people, it’s neutral and not a big deal. These comments show the underlying cultural belief that disability is bad, and to be avoided, rather than a natural part of life. This can also make people believe that people with disabilities are helpless, rather than acknowledging their abilities and what they are able to do and contribute. Feeling sorry for someone also does nothing to actually improve their lives. They would rather you be upset and take action regarding discriminatory actions and lack of access and opportunities.

- “Lighten up, it was just a joke.”

- “You’re too sensitive.”

- “Don’t let your disability define you.”

- “You’re making a big deal out of nothing.”

- “People will listen more if you’re nicer.”

- “You’ll get more flies with honey than vinegar.”

- “I didn’t mean it that way, can’t you take a joke?”

- “You need to have a sense of humor about [your disability].”

These types of comments diminish the feelings of people with disabilities, and prioritizes other people feeling comfortable over treating people with disabilities with dignity. It says that people being upset by unfair treatment is the problem, not the unfair treatment itself. This is also called tone-policing, where people will ignore your valid concerns if they are not expressed in the “proper” way, which in most cases means having no emotion. Discussions about disability rights are not just fun philosophical exercises; they have real consequences on the lives of people with disabilities. It is easy not to be emotionally invested in a topic if it does not affect you personally. Instead of asking someone to change their tone, ask yourself why the topic is so important to the speaker, and try to hear their arguments and understand their perspective.

- “You’re an inspiration.”

People with disabilities find people celebrating their modest achievements, such as clapping when someone with crutches walks across the street. This communicates low expectations about what people with disabilities can achieve. Everyday activities may be harder for people with disabilities, but they don’t want a medal for going to the grocery store. They want appreciation, gratitude, or respect for what they are able to achieve. These kinds of messages also put pressure on people with and without disabilities to “just try harder – if those poor disabled people can do it, so can you!” It minimizes people with disabilities to a stereotype of what they are unable to do, rather than seeing them as an individual full of potential.

- “I don’t see you as disabled.”

You may think you are saying that you appreciate someone and don’t see their disability as the only part of their identity, but the underlying message says: it’s convenient for me to ignore how disability effects your life. We would rather pretend disability doesn’t exist because that’s more comfortable than addressing how people with disabilities are denied opportunities in our society. Ignoring a problem rarely makes it go away, and erasing or ignoring a part of someone’s identity is disrespectful.

Language, including body language, can be a microagression. Using non-inclusive language is a microaggression, as well as avoiding eye contact, looking through a person like you don’t see them, or staring.

One goal of the ADA is for people with disabilities to enjoy greater integration and opportunities in our communities. Microagressions make people feel like they don’t belong and are less than. These attitudinal barriers can be just as harmful to people with disabilities as physical barriers. Unlike other mandates in the ADA, our language choices are something every one of us can address in our personal lives. I hope you will use this information to start a discussion about disability with your family, friends, or coworkers, and how access and disability affect us all.