My Heart Attack

One night, not too long ago, I woke up with great pain in my chest. I was hesitant to go to the hospital as we were in the middle of the COVID-19 lockdown. I was also hesitant and unsure of the conditions at the hospitals. After a few hours, the pain went away. I woke up a few hours later, feeling just fine. The memory of the pain that I had experienced a few hours earlier lingered. I started doing what I loved to do, working for the Rocky Mountain ADA Center, from home. Colorado, at that time was under Safer at Home order by Governor Jared Polis.

At the end of the day, after I completed my tasks and was shutting down my computer, the congestive pain returned. Much sharper and piercing this time! I had to lie down, in the hopes that the pain would go away like earlier that morning. I kept losing consciousness, so I had to page my wife—who was working downstairs at that time—for help. I knew that—COVID or not—I had to go to the hospital.

As a Deaf person, choosing the right hospital was important. One might wonder why choosing the right hospital was important. In my town, there are a couple of hospitals and it is from my work at the RMADAC that I know which hospitals would provide live interpreters and which would not. It was because of that knowledge that I asked my wife to take me to a hospital a bit further than the one closest to my home. The hospital closest to my home has a record of failing to provide effective communication for Deaf patients. On-site interpreters are usually the preferred option for most Deaf patients.

On the way to the hospital, I kept losing my vision, which could have been from the lack of oxygen that I was experiencing. When we arrived at the emergency entrance, the hospital staff was highly efficient administering the necessary procedures. With what little vision I had, I was able to discern that my wife signed to me in ASL that I had a heart attack and would require surgery. I recalled going through what seemed to be miles of corridors to the surgery room before I lost consciousness.

Hospital Communication

A while later, after I regained consciousness in the ICU, I saw several hospital staff around me. A nurse brought a tablet to me. On the tablet was an ASL interpreter. I could not fathom what the interpreter was signing to me because I was still groggy. I recalled feeling upset and waved the nurse with the tablet away. I waved the nurse away as I could not focus nor understand what the interpreter on the tiny screen was saying. I was still light-headed from surgery and going in and out of consciousness. This was a definite break from reality for me.

When I woke up a while later, a nurse came to see me. I could see that she was trying to tell me something about my son calling for my wife to see how I was. Even though I am adept at lipreading, because I was in pain, I was unsure if I had lipread the nurse correctly. Being a part-time adjunct professor in Deaf culture and Deaf Studies, I am very aware of several research articles showing that lipreading is mainly guess work. Only 30% of the English Language can be clearly understood on the lips. The rest is guess work, depending heavily on the context. Out of frustration, my wife managed to convince the hospital to loan me an iPad with which we FaceTimed each other. It was heaven for us to communicate directly with each other without having to rely on people passing messages between us.

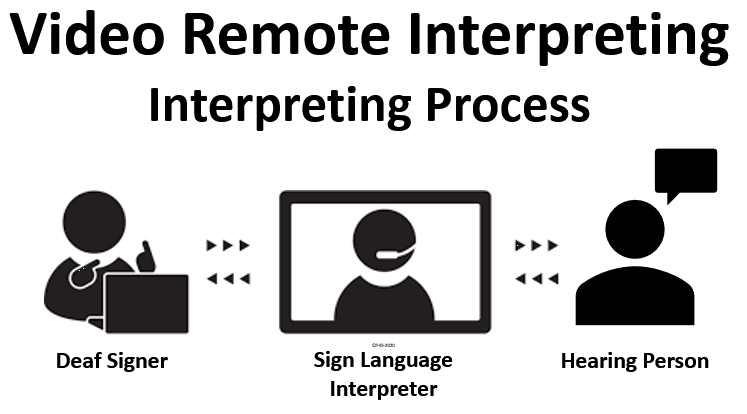

While on FaceTime with my wife, an interpreter came into my room, I was thrilled! Now, I could communicate freely with whomever I needed to at the hospital. The interpreter told me that he was about to be sent away as the hospital thought that they could use their VRI (Video Remote Interpreting) app to facilitate communication with me. VRI is a videoconferencing app that can be used on laptops, tablets, or smartphones using sign language interpreters remotely.

With VRI, the Deaf person will sign to the interpreter through the video technology and the interpreter will voice for the Deaf person, the interpreter will then listen to what is being said and sign to the Deaf person. Basically, VRI is the same as the Video Relay Service (VRS) which allows Deaf people to make and receive phone calls using sign language interpreters at call centers that are located throughout the United States. The only difference between VRI and VRS is that VRI is a paid interpreting service and VRS is a federally funded interpreting service. VRS was developed to remove barriers for Deaf people with telecommunications as mandated by Title IV of the ADA.

Effective Communication

When the ADA became law in 1990, Title IV of the ADA focused on ensuring that intrastate telecommunications was accessible to persons with hearing disabilities through TRS (Telephone Relay Service). In 1990, TTY (TeleTYpewriter) and TDD (Telecommunications Device for the Deaf) were used to make and receive calls. TRS used operators to read and verbalize TTY/TDD messages from Deaf people and type the spoken messages. That was how TRS worked and was quite cumbersome as the speed of typing could not match the speed of speech. Over time, with new and improved technology, videophones which allow sign language interpreters to relay messages gained popularity. The time taken to convey messages was significantly reduced. This allowed for near real-time communication to take place.

While VRI might appear to be a wonderful use of technology to bridge communication barriers, this has been very unpopular and often ineffective for Deaf people in hospital settings. I use VRI often at work for meetings and when I occasionally need an interpreter at the last minute. Although VRI is seen as an auxiliary aid under the ADA Effective Communication requirement, VRI is ineffective in some cases, especially in medical situations. My hospital experience gave me first-hand experience on why VRIs can be ineffective. This is starkly illustrated by the nurse attempting to use VRI on the tablet when I was still waking up and was not fully alert.

Getting An Interpreter

The interpreter was in the lobby and was told that a “Deaf patient” needed him, which must have been me when I got upset. Although the interpreter had a face-mask with a clear plastic covering to facilitate lipreading, I found that the transparent opening in the face-mask made only a slight difference. Apart from the face-mask, the interpreter made a world of difference. Even the hospital staff noticed the fluidity of communication that occurred between me, my doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff.

When my cardiologist came to see me and check on how I was, at that moment, I felt good, just as if I did not have a heart attack. But I was experiencing a piercing and congestive pain in my left kidney. The doctor was visibly alarmed and immediately sent me to have an MRI taken. After the MRI procedure, another doctor explained to me that it is quite common for plaque to be dislodged in kidneys of heart attack patients. Such plaque, when dislodged, typically form clots. Again, the interpreter effortlessly facilitated the communication between me and the doctor with minimal chances of any misunderstanding. As a result of the MRI and identification of the clot, I was put on a regimen of medication and blood thinners. I was also required to stay overnight at the hospital for observation.

I requested that the same interpreter return the next day to ensure effective communication since he was cognizant of my situation. Normally, interpreting agencies tend to send whoever is available to interpret at any day and time unless a specific request is made. The interpreter returned the next day and the day after as I ended up staying at the hospital for three days.

Although no one likes to be “stuck” in a hospital, I must say that as a Deaf person using ASL, my communication experience was so much better with the presence of an on-site interpreter. An efficient and smooth flow of communication was maintained all around. By having effective communication with my doctor and the hospital staff, my life was probably saved. This could be due to my ability to describe the pain I was feeling in detail. The interpreter allowed me to be fully informed about why I was having pain in my kidney. I also learned that plaque does not exist only in my mouth but in my kidney as well.

Lessons from my experience at the hospital:

- Clear openings in facemasks are not 100% effective as parts of the mouth/face may be obscured and not all Deaf patients are adept in lipreading

- Many people and entities believe that technology can substitute the human touch

- Having the same interpreter remain with the Deaf patient from the start of their hospitalization is helpful in maintaining consistency

- VRI does not work for all patients who are not focused, who are in pain, or are not alert

- On-site interpreters are more cognizant and aware of a patient’s state of alertness and would be better able to ensure that the Deaf patient can comprehend whatever is being spoken

- Hospitals need to have staff who are proficient in the use of VRI equipment

- VRI may be useful as a temporary solution in hospitals for immediate communication while waiting for an on-site interpreter to arrive

The ADA Business BRIEF: Communicating with People Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing in Hospital Settings is a good guideline to use.

Situations where an interpreter may be required for effective communication:

- Discussing a patient’s symptoms and medical condition, medications, and medical history

- Explaining and describing medical conditions, tests, treatment options, medications, surgery and other procedures

- Providing a diagnosis, prognosis, and recommendation for treatment

- Obtaining informed consent for treatment

- Communicating with a patient during treatment, testing procedures, and during physician’s rounds

- Providing instructions for medications, post-treatment activities, and follow-up treatments

- Providing mental health services, including group or individual therapy, or counseling for patients and family members

- Providing information about blood or organ donations

- Explaining living wills and powers of attorney

- Discussing complex billing or insurance matters

- Making educational presentations, such as birthing and new parent classes, nutrition and weight management counseling, and CPR and first aid training