Growing Up in South Africa

At the end of the 20th century, I was a young and bright-eyed Deaf activist from South Africa fighting for our rights to equal communication. Along with other young Deaf people we founded our own organization to fight for change. We faced several barriers. South Africa in the 1990s was grappling to free itself from racial oppression that had started several centuries earlier. Additionally, South Africa had a myriad of unjust race segregation laws developed under the nomenclature of apartheid. Apartheid was a system of laws and policies that were developed when the Afrikaner Nationalist Party got voted into Power in 1948.

This racial oppression trickled down oppression in other forms including disability oppression. Disability oppression is one of the reasons that the oft quoted adage “Nothing About Us, Without Us” was adopted. This well-known maxim was used by two South African disability activists, Michael Masutha and William Rowland, in 1993. This quote had a fascinating history before it came to embody the struggles of the Disability Rights Movements worldwide. This history is covered by James Charlton in his 1998 book, Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment.

Deaf President Now Movement

While we were challenging the system that prevented equal access to us South Africa, we learned about the Deaf President Now (DPN) protests. These protests were taking place at Gallaudet University in Washington D.C. in the USA. We learned that students at Gallaudet University had successfully protested the selection of the University’s 7th and first female President in Gallaudet University’s 124-year history.

I would need to interject here that the charter that allowed Gallaudet University to grant Deaf people college degrees was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on April 8, 1864. Several other universities established for specific populations successfully had presidents of such populations they represented. Gallaudet University did not yet have a representative Deaf president in all its years of existence. The Deaf students at the University were upset when the Board of Trustees ignored their request for a Deaf person as their next president. So, students shut down the University for a week. The university was opened when Dr. I. King Jordan, a Deafened man was named the first Deaf President of Gallaudet University on Sunday, March 13, 1988.

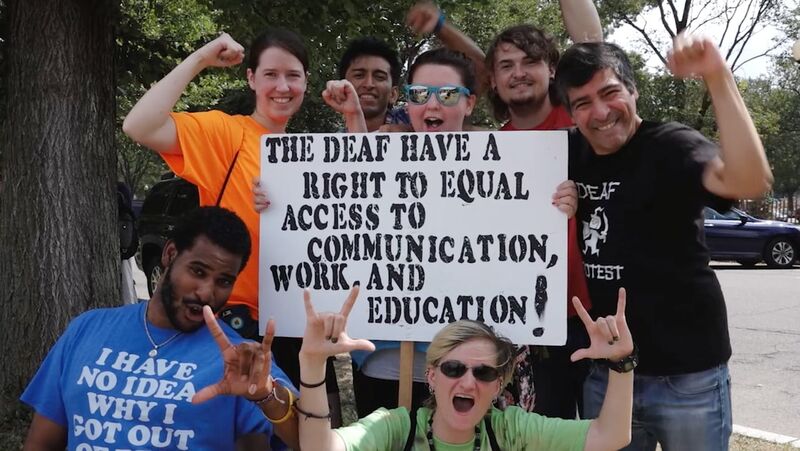

The Fight for Civil Rights

By the late '80s, people with disabilities in the United States had long fought to have their civil rights enshrined in the law along with the other rights granted by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The implications of the Deaf President Now protest brought much attention to the rights of people with disabilities who were still being marginalized. So, after the DPN, Senator Tom Harkin (D) from Iowa, brought forward the "Americans with Disabilities" bill to the senate floor, it passed with a vote of 76 to 8. Senator Harkin had a Deaf brother and saw his brother’s frustrations while growing up.

So, in a way, Gallaudet University’s Deaf President Now movement might have given the ADA some impetus into becoming the law of the land. The ADA prohibits discrimination against anyone based on their disability. The ADA became law on July 26, 1990.

Moving to the U.S.A.

Meanwhile in South Africa, this DPN movement inspired us to continue our fight for equal access in South Africa. Although, my compatriots and I were quite successful in breaking down some barriers for Deaf people in Johannesburg, there were still so many more barriers to face and I felt exhausted. Being an activist can take so much energy from a person.

Although I was a proud 5th generation South African on both sides of my family, I decided to move to the United States in the mid-1990s to join my family who were already attending Gallaudet University. I arrived at Gallaudet University under a cloud of sadness as my dear Deaf sister had just passed on, but I felt honored to walk down the hallowed halls where so many other Deaf people had the opportunity to tread before me.

Disability Law

While the United States was a whole new country for me, I felt that there were a lot of parallels in the lifestyles we led. It is important to note here that I acknowledge the privileged lifestyle I had lived in South Africa as a white person with a father who was well known and much admired for his achievements. My father was the first Deaf person to complete high school and to graduate with a doctorate from South Africa’s most prestigious medical school. When I arrived in the USA, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was in its infancy, having just celebrated its 5th year since becoming the law of the land.

While in the United States, I saw that communication access for Deaf people was so much more accessible. Another big plus for me was that almost all videos and prime time television were captioned. I was also fascinated with the Telephone Relay System (TRS) that allowed Deaf people to make and receive telephone calls.

For the next 4 years I immersed myself with my studies at Gallaudet University, learning so many things. At the forefront of my interest while studying was how the law applies to people with disabilities, and Deaf people in particular. Upon graduation, I found work as a social studies teacher at a school for the Deaf which led me to study for my second graduate degree, this time in Deaf Education as I was curious to know more about the laws that governed education for Deaf children.

Thanks to the ADA

Like my father, I became a college professor. Over the years, my interests always returned to how the law affected people with disabilities. While teaching at Gallaudet University, I developed a course—International Disability Rights Movement—which allowed me to focus on my passion and teach others about the history behind the ADA and its impact. Many people may not realize it, but the ADA was a direct influence on the formation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) which was opened for signature in 2007 and came into force in 2008.

As of January 2020, there were a total of 182 countries—including the European Union—which recognized the CRPD. Of the 182 countries, 163 became signatories to the CRPD which alludes to their intention to comply with the CRPD. So, it is thanks to the ADA that the lives of people with disabilities not just in the United States but worldwide have improved and their civil rights are protected.

When my wife and I travel to different countries, by virtue of my job with the Rocky Mountain ADA Center, I tend to pay more attention to accessibility for people with disabilities in these countries. Accessibility in some countries is dismal, while others may be better, but none manage to meet the degree of accessibility afforded to people with disabilities in the United States. After each travel abroad, my wife and I agree that while we still face challenges, it is thanks to the ADA that our lives are made more accessible and as a result, better!